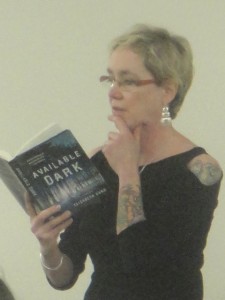

winner of the 2012 Shirley Jackson Award for her novella “Near Zennor,” reading at the University of Central Florida in March, for Available Dark.

Elizabeth Hand

July 26th, 2012 § 0 comments § permalink

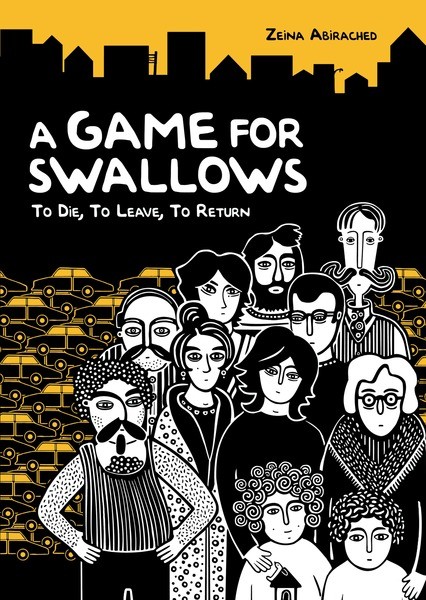

A Game for Swallows by Zeina Abirached

July 24th, 2012 § 0 comments § permalink

I’ve blogged about this before, but now the August 1st release date is finally nigh, I’d like to give another shout out to Zeina Abirached’s terrific graphic novel A Game for Swallows from Lerner Books. Words Without Borders featured the first ever English excerpt from the book in Feburary 2010, and PEN America, the journal of the PEN Foundation, soon published another. In 2010, A Game for Swallows was the first graphic novel to be selected for a grant by the French Voices Program from the French Embassy, and this year, it was named a Junior Library Guild selection. Indefatigable Brit comic blogger Paul Gravett did an excellent interview/article in January of this year (featuring uncredited pages cribbed from WWB), which details some of Abirached’s background, the book’s publication history in France with Éditions Cambourakis, and the impetus for its creation, which the author makes the centerpiece of the book’s expanded preface.

At first glance, the parallels between Abirached’s Swallows and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis are obvious, and probably something many critics will remark on: memoirs of childhood by Middle Eastern girls drawn in a black and white, deliberately naïve style. To be slightly cynical, ever since Persepolis, American publishers have been looking for the next French graphic novel that would prove as big as Satrapi’s hit. But Abirached’s page layouts are much more formal, decorative, geometrically inspired, even ceremonial. One could even liken them to the wall hanging in the foyer of the family apartment that is one of the book’s major motifs.

Swallows takes place over the course of a single night in the safest (read: windowless) room of an apartment against the backdrop of war-torn Beirut. It eschews the chronological progression of most memoirs for a frame story: Abirached’s parents are off visiting her grandmother, while the children are at home with Anhala, a maid who’s been in the family for generations. When a sudden bombardment forces the parents to stay at the grandmother’s till the streets are safe again, the children are trapped at home, in a foyer that quickly fills up with neighbors seeking shelter. Carefully characterized with quirk, distinctive physical features, and anecdotes that have the ring of truth, these neighbors form a precarious community that makes a great stand-in for that of the besieged city at large. Tensions and tempers rise and fall in this huis clos, but objects and moments also serve as excuses to delve into memories, personal histories; in fact, memories (and to a lesser extent, imagination) are the only way out, the only way to transcend perilous and limiting circumstance, a fact that is in no small way the source of the book’s melancholy. » Read the rest of this entry «

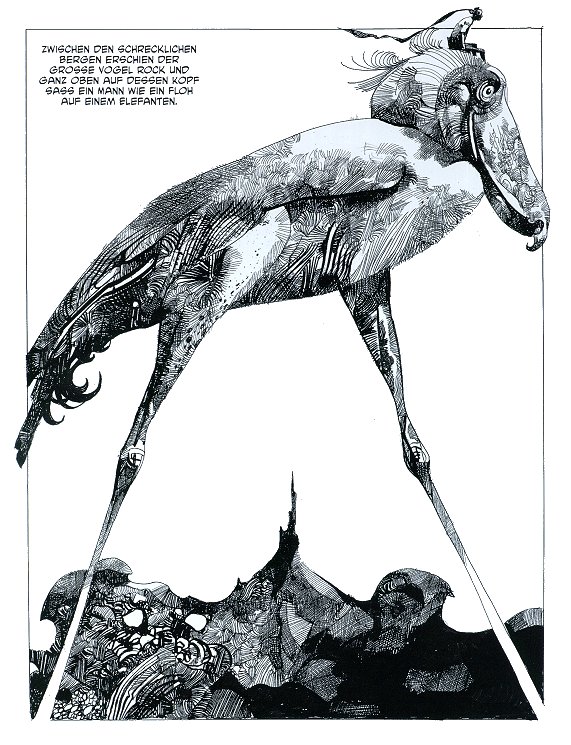

The Thousand and One Arabian Nights Like You’ve Never Seen

July 22nd, 2012 § 1 comment § permalink

This fall, Archaia comics will be kicking off a run of works by (Sergio) Toppi, the Italian comics master, with his graphic novel Sharaz-De, an adaptation of the Arabian Nights, prefaced by no less than Walt Simonson. Archaia’s got some choice preview pages up, as does Miguel at Comics Without Borders, who blogged about this book around the time I would’ve started work on it. Mythic, hieratic, seductive, organic, geometric, epic, alarming, unearthly, blowing the concept of panels to smithereens with sweeping page layouts, Toppi’s art lends a daunting alien majesty to this classic. Too bad he never illustrated Calvino.

Congratulations to the 2012 Science Fiction & Fantasy Translation Award Winners!

July 21st, 2012 § 0 comments § permalink

The Association for the Recognition of Excellence in SF & F Translation (ARESFFT) is delighted to announce the winners of the 2012 Science Fiction and Fantasy Translation Awards (for works published in 2011). There are two categories: Long Form and Short Form. The jury has additionally elected to award two honorable mentions in each category.

Long Form Winner

Zero by Huang Fan, translated from the Chinese by John Balcom (Columbia University Press)

Long Form Honorable Mentions

Good Luck, Yukikaze by Chohei Kambayashi, translated from the Japanese by Neil Nadelman (Haikasoru)

Midnight Palace by Carlos Ruiz Zafón, translated from the Spanish by Lucia Graves (Little, Brown & Company)

Short Form Winner

“The Fish of Lijiang” by Chen Qiufan, translated from the Chinese by Ken Liu (Clarkesworld #59, August 2011)

Short Form Honorable Mentions

“The Boy Who Cast No Shadow” by Thomas Olde Heuvelt, translated from the Dutch by Laura Vroomen (PS Publishing)

“The Green Jacket” by Gudrun Östergaard, translated from the Danish by the author and Lea Thume (Sky City: New Science Fiction Stories by Danish Authors, Carl-Eddy Skovgaard ed., Science Fiction Cirklen)

The winners were announced today at Finncon 2012 < http://2012.finncon.org/>, held in Tampere, Finland. over the weekend May 19-20. The awards were announced by jury member Irma Hirsjärvi and ARESFFT Board member Cheryl Morgan.

The winning authors and their translators will each receive an inscribed plaque and a cash prize of $350. Authors and translators of the honorable mentions will receive certificates.

Jury chair Dale Knickerbocker said, “The jury would like to thank all who nominated works, and compliment both the authors and translators for the fine quality of this year’s submissions. While both the winner and honorable mentions in the long fiction category had their supporters, we ultimately chose Huang Fan’s novella Zero (translated from the Chinese by John Balcom) as the winner. The author skillfully weaves elements from the masterpieces of dystopian fiction into his own very unique text, and the translator successfully communicates the work’s stark, frightening nature. Zero’s surprise denouement takes Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle a step further, wedding it with a touch of Asimov’s The Gods Themselves.”

“This year’s winner in the short fiction category, Chen Qiufan’s “The Fish of Lijiang” (translated from the Chinese by Ken Liu) was described by our judges as “brilliant,” “original,” and “a lovely and devastating story, beautifully written and translated.” It presents an interesting take on mental illness and wellness, work, and future technologies. In the tradition of the best SF, it offers a convincing extrapolation of the economic and consequent social changes that China has undergone in the past 30 years.”

ARESFFT President Professor Gary K. Wolfe added: “I’m delighted that the hard work of our distinguished jurors has resulted in such an impressive list of winners and nominees, and–equally important–that the international science fiction and fantasy community has taken this award to heart in terms of supplying nominees and suggestions for nominees. Congratulations not only to the winning authors and translators, but to everyone who has helped make these awards a viable and invaluable project.”

The money for the prize fund was obtained primarily through a 2011 fund-raising event for which prizes were kindly donated by George R.R. Martin, China Miéville, Cory Doctorow, Lauren Beukes, Ken MacLeod, Paul Cornell, Adam Roberts, Elizabeth Bear, Hal Duncan, Tansy Rayner Roberts, Peter F. Hamilton, Ann & Jeff VanderMeer, Nalo Hopkinson, Juliet E. McKenna, Aliette de Bodard, Nicola Griffith, Kelley Eskridge, Twelfth Planet Press, Deborah Kalin, Baen Books, Small Beer Press, Lethe Press, Aeon Press, Jon Courtenay Grimwood, Kari Sperring, Helen Lowe, Rob Latham and Cheryl Morgan.

The jury for the awards was Dale Knickerbocker (Chair); Kari Maund, Abhijit Gupta, Hiroko Chiba, Stefan Ekman, Ekaterina Sedia, Felice Beneduce & Irma Hirsjärvi.

ARESFFT is a California Non-Profit Corporation funded entirely by donations.

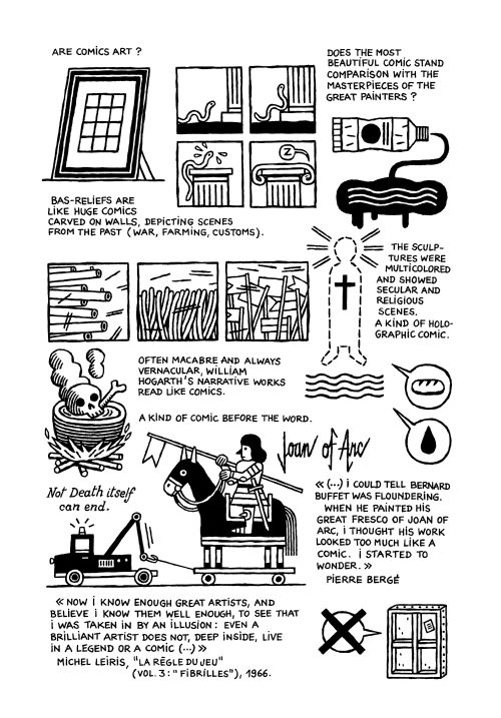

Archival: Jochen Gerner’s Contre la B.D.

July 18th, 2012 § 0 comments § permalink

(In July 2009, Words Without Borders published an excerpt from Jochen Gerner’s critical nonfiction comic Contre la B.D.—specifically, part of the chapter entitled “Against Art.†It’s a thought-provoking piece that’s gotten some nice notice around the web. There’s a good essay available in French and English on it at du9, a site devoted to the 9th art, comics.

In the “Archival†rubric of this blog, which I’m launching with this entry today, I’ll be returning for brief considerations of works I’ve already translated, for any number of reasons: to provide greater context on a piece, to say something I wish I could have at the time, to publish thoughts edited out of other articles, to share things I’d now do differently, to find a home for musings rejected elsewhere. Orphan thoughts, or stragglers.)

Jochen Gerner’s book-length comics essay Against Comics (L’Association, 2008) could plausibly be read as part of what Canadian comics scholar Bart Beaty calls the “postmodern project†of the “contemporary European comic book avant-gardeâ€: namely, to “consecrate the comic book form through a reinvention of its low-culture elements and association with consecrated aspects of modernism.†In the July issue’s excerpt from the chapter entitled “Art,†Gerner holds comics, that most populist of art forms, up to Pop Art, finding the latter wanting and, worse yet, overpriced, exposing not only a long-running hypocrisy in society’s attitude toward comics, but how permeable, even susceptible, disciplines once thought distinct are to each other’s influence. On Gerner’s pages, works of art are imported to the comics realm in deliberately, characteristically cartoonish renderings, as though all comics, or at least Gernerland, were a unified geography, and by going there we ourselves would be Gernerized. At the same time, Gerner abandons the meticulously gridded layout, known in French as the “waffle iron,†that he uses in books like Court-circuits Géographiques and (Un Temps.), thereby liberating the page from panels and sequence, two basic elements often used to define the medium. In pushing the boundaries of a form not usually associated with nonfiction, Gerner creates something like a museum on paper, where art is recontextualized in a comics setting; invited into this contemplative space without prescribed route, the reader’s eye freely saccades from quote to image down pages as much argument as collage.

Take a step back, and the strategy is further complicated: as Beaty notes in his pioneering study Unpopular Culture, comics’ acceptance in Europe was evidenced “increasingly, by the incorporation of comic book art into museums and gallery spaces that had long excluded them.†Published by L’Association (the driving force behind the French alt comics renaissance of the ’90s and ’00s), and active in OuBaPo (the comics equivalent of Oulipo), Gerner was one of several artists, central to the French comics avant-garde, whose work brought about this acceptance. Indeed, Against Comics (Contre la B.D.) is at times so culturally specific in its cultural references, and the fights it picks, that one hesitates to translate B.D. (bande-déssinée) as “comics.†In a global age when beggared English grows by borrowings, it seems useful to be able to employ both freely, and not be misunderstood, much as we already differentiate between comics and manga. New words may be needed to keep up with a medium reinventing itself in distinct cultural traditions around the world, each interrogating their own origins and limits, the better to evolve and astonish.

RC Himself

July 17th, 2012 § 0 comments § permalink

Robert Crais reads from Taken, the latest Elvis Cole – Joe Pike novel, at Vroman’s (Pasadena) in January.

Kim Stanley Robinson

July 13th, 2012 § 0 comments § permalink

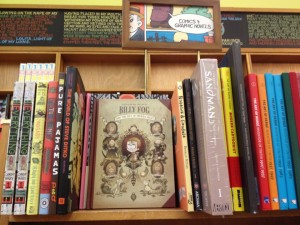

Overlooked, but not forgotten

July 11th, 2012 § 0 comments § permalink

A truth of the book biz: Sometimes it takes a while for a title to grow or catch on, and often books get lost in the shuffle because marketing couldn’t quite give them the push they needed, for whatever reason: understaffed, underbudgeted, overworked. I have a great deal of fondness for Billy Fog–heck, I’ll probably be devoting my panel contribution to it at the American Literary Translators Association conference this fall–and thus far have completed three volumes of it. I think of it as Edward Gorey meets Calvin & Hobbes: original, haunting, alarming, and poignant. But heck, even I’m half a year late in posting this fine review of it from the folks over at The Onion A.V. Club:

French cartoonist Guillaume Bianco recalls Roald Dahl, Shel Silverstein, and Edward Gorey with his album Billy Fog: The Gift Of Trouble Sight (Archaia), about a death-obsessed little boy who sees ghosts and demons that others can’t. Combining illustrated poems, fake newspapers, games, factoids, conventional comics, and first-person musings by his hero, Bianco’s book may seem a little dense and disconnected at first, but there is an actual story tying all these fragments together, having to do with the death of Billy’s cat and how it gets him thinking about souls, Santa Claus, and whether all grown-ups are murderers because “they killed the kids they used to be.†The Gift Of Trouble Sight is macabre, but never excessively so, and as Billy comes to grips with the permanence of death, Bianco achieves a profundity rare for this genre.

The 2011 List

July 8th, 2012 § 1 comment § permalink

Last year was, alas, a light one for reading, and got lighter as the year went along and involved multiple moves, the start of a grad program, juggled priorities. As usual, only whole books, not individual stories, are listed, and though I was better about listing graphic novels, many of them (as asterisked) were read for work. It’s a pretty random grab bag; here’s to 2012 being a better reading year, quantitatively.

Georges-Olivier Châteaureynaud, Mathieu Chain

Philip K. Dick, UBIK

Graham Joyce, The Silent Land

Jeff Abbott, Panic

Georges-Olivier Châteaureynaud, Résidence dernière

Margaret Atwood, The Blind Assassin

Serge Brussolo, Trajets et itineraires de l’oubli

Paul Willems, La cathédrale de brume

Jacques Gélat, Le traducteur

Nadine Monfils, Contes pour les petites filles perverses

Paul Willems, La vase de Delft

Patrick Besson, L’orgie échevelée

André-Marcel Adamek, Contes tirés du vin bleu

Kim Connell, ed. The Belgian School of the Bizarre

Steve Almond, My Life in Heavy Metal

Sylvain Jouty, Queen Kong

Serge Brussolo, 3, Place de Byzance

Serge Brussolo, Le syndrome du scaphandrier

Jean Ray, La Cité de l’indicible peur

André-Marcel Adamek, Le maître des jardins noirs

André-Marcel Adamek, Retour au village d’hiver

Christian Bobin, La dame blanche

Thomas Gunzig, Il y avait quelque chose dans le noir qu’on n’avait pas vu

André-Marcel Adamek, Oxygène

Hope Mirrlees, Lud-in-the-Mist

Thomas Gunzig, Take Five

Maurice Pons, Chto!

Maurice Carême, Médua

Tom Piazza, My Cold War

Francis Spufford, The Child That Books Built

Guillaume Bianco, Billy Brouillard: Le don de trouble vue*

Jean-Pierre Pécau & Igor Kordey, L’Histoire Sécrète 15-21*

Jean-Pierre Pécau & , Arcanes 1-5*

Matz & De Meyere, Cyclops 4*

Marjane Satrapi, Le Soupir*

Jennifer Egan, The Keep

Lev Grossman, The Magicians

Cory Doctorow, Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom

Maranzano & Ponzio, Genetiks 1*

Alex Alice, Siegfried 1*

Lev Grossman, The Magician King

Jonathan Carroll, Bones of the Moon

Ludovic Debeurme, Renée*

David B. & J.-P. Filiu, Les meilleurs ennemis*

Margaux Motin, J’aurais adoré être ethnologue*

Maurice Pons, Mademoiselle B.

Noël Devaulx, Frontières

Penelope Bagieu, Cadavre exquis

Dylan Horrocks, Hicksville

Kim Deitch, The Boulevard of Broken Dreams

Bernard Quiriny: Une collection très particuliere

July 2nd, 2012 § 4 comments § permalink

“For some time now, distances have been increasing: all other things being equal, each day streets grow longer, suburbs farther from downtown, apartment complexes farther apart.†With these words, Bernard Quiriny begins his chapter “Deglomeration,†the fifth in a category entitled “Our Era.†The Belgian fabulist’s latest book, which I hesitate to describe as a story collection, is divided into three such categories, the other two being “Ten Cities†and “A Very Curious Collection,†which lends its name to the book as a whole.

“Ten Cities†is exactly that: ten brief, fanciful descriptions of cities real and imagined, or imagined aspects of real cities, from around the world (with the exception of Asia and Africa), sometimes narrated by the author’s recurrent character, Pierre Gould, and at other times presented as personal experience. More often than not they take the form of recounted travelogues or unattributed, guidebook-style information. They range in length from a single, two-line sentence to six or seven pages.

The entries in “A Very Curious Collection,†each thematically titled, are all presented by Gould, as he introduces the narrator to another section of his unique library. These sections, each containing one kind of book (and usually its opposite), are as eclectic as they are whimsical: books their authors have forgotten they wrote (and books authors wish they could forget, and books that are forgettable altogether); the most boring books ever written (both intentionally and not); puzzle novels (Russian nesting novels, recombinatory novels) always containing more than they appear to; books authors have tried to disown or destroy (including a notebook of Gould’s containing a novel he rejected before he ever finishing it); books impossible to read except in formal attire; specialized cookbooks (recipes for stomach trouble, recipes for skin reactions, impossible recipes); books that continue to correct themselves, quietly pursuing their revision toward perfect economy (which also means they grow shorter); books that have saved lives (and taken them); books that can act as batteries and power lamps; books that have swallowed their authors, who keep writing them from within; books like yard sales full of bric-a-brac, redeemed and made endearing by an unexpected find.

As for “Our Era,” these observations on new phenomena and their effect on contemporary society range from mass resurrections, cross-gender bodyswapping, and willful name-changing to youth serums and an infiniverse of parallel realities being created every minute by every act, no matter how insignificant.

If I seem, with these categories, to have described a book so wonderful it cannot possibly exist, that is at least partly true. A fan of the author’s work, I looked forward to this book and ultimately wanted to like it more than I did. It plays like the trailer of an impossibly good movie that, alas, we will never see, because it does not exist. And so A Very Curious Collection is by turns intriguing, exasperating, brilliant, titillating, dilettantish, cavalier, but always elusive, ever pointing outward to something greater than the sum of the disparate parts it leaves you with. Its ideas are often as half-baked as they are arresting, at worst dashed-off, at best reflecting the wit, fun, and exuberance of Quiriny’s restless experimentation, lab notes from his mad lab. There are no real standalone stories in this book; rather, the closest American market category of writing to Quiriny’s is the upscale humor essay, which often departs from a whimsical premise. Quiriny, whose targets for affectionate satire are taken less from real life than from other books, is something like a feuilletoniste of experimental literature. His satire is hit or miss, buoyed along by his nonstop invention; the real trouble is that by failing or refusing to follow up on his ideas, he has made few of them memorable.

Nevertheless, there are moments of genius. “Deglomeration,” the gradual spatial expansion of the world, begins with a hand reaching out to snooze an alarm clock and missing, “the nightstand having retreated five inches in the night.†A garage grows to the size of a tennis court. Rooms suddenly larger are partitioned into smaller ones.

That it takes increasingly longer to get anywhere reflects something of the world we know: transport that once made the world smaller is subject to congestion and delays, cities recover some of their scale when foot traffic becomes the main means of locomotion. Things seem farther apart again; Quiriny has merely literalized this experience in geography. When the distance between Concorde and Charles-de-Gaulle lengthens, more metro stops pop miraculously up to divvy up the distance into more customary intervals.

And yet, Quiriny is careful to note, “Strangely, this transformation is not accompanied by any creation of new matter. From space, the Earth does not seem to grow: photos prove this.†He returns to tweak reality on the level of absurd mundane detail at which he excels. Fields for sporting events must be redrawn before each game; delivering food amounts to a cross-country rally; real estate is a wiser investment than ever, since houses grow along with their families. Ireland, Japan, and Australia are largely unaffected. England and Scotland are among the slowest growers.

Soon, Quiriny’s narrator reflects, “we will each wind up alone on our own vast stretch of land, growing farther every day from everyone else’s.†Which is as fine a metaphor as I’ve found for the isolation, the loss of community, contemporary critics blame on our increasing ability to select and filter what we receive from our environments (usually media). “Once, visionaries believe the human race, its numbers growing every day, would have to leave Earth and colonize another planet. They were wrong: in reality, all you have to do is walk a little ways to find immense virgin spaces where you can found your own personal kingdom.†Inner space; the literalization of the virtual.

Quiriny finishes by acknowledging the temporal aspect of the experience he has literalized in physical space with a joke I find oddly moving. A remix of the classic Verne novel has become a bestseller: Around the World in Eighty Years, in which it takes three generations, grandfather to grandson, to round the globe, a feat as monumental as building a cathedral. That took a village too, though not a global one.