January 30th, 2013 § § permalink

As every comics fan out there knows, this coming weekend is the madness of the Angoulême International Comics Festival (now in its 40th year!). I wish I were there, but barring that, I can at least plug a project I’ve recently become involved in.

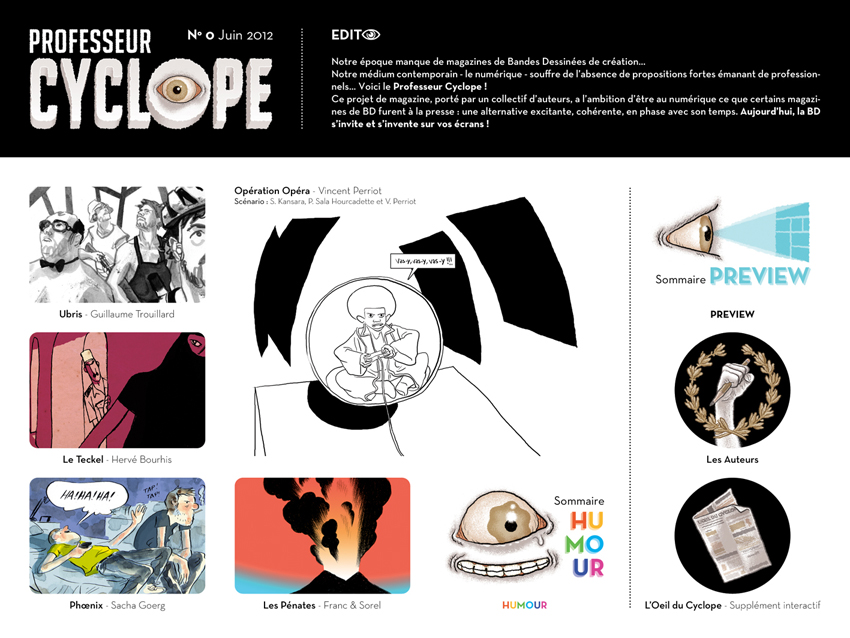

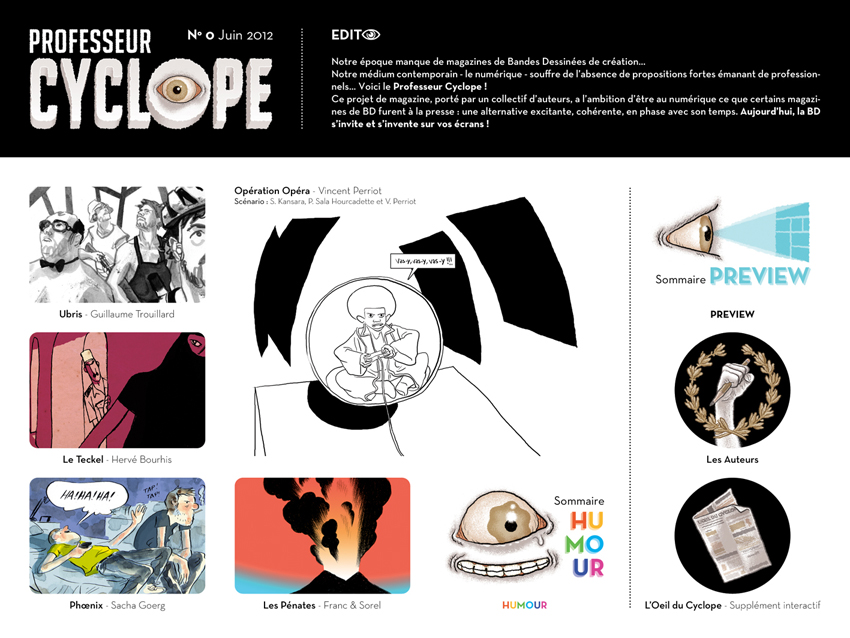

Professor Cyclops is a brand new comics revue conceived expressly for the digital experience, with all manner of multimedia extras. The brainchild of a handful of France’s top young creators—Gwen de Bonneval, Hervé Tanquerelle, Brüno, Marc Lataste, Cyril Pedrosa, and Fabien Vehlmann—it’s meant to fill the periodical gap in quality, creator-driven comics, covering the spectrum from avant-garde to genre, RAW to 2000 A.D.

I’ve been translating some of the business documents for this exciting venture, and I do have to say: these boys think big! They’ve already partnered with Franco-German TV channel Arté, which guarantees high-profile funding, but what they’re really looking to do is make comics a regular choice in the entertainment spectrum. They’re very close to realizing their dream of a comics magazine for all ages and all readers being available in the virtual kiosk of major airlines, or an option among pay channels on hotel TVs.

Readers can catch a glimpse of what’s to come in the magazine, due to debut this March. On Friday, February 1, 2013, at 11:30am in the Salle Odéon du Théâtre d’Angoulême (Avenue des Maréchaux), all five founders will be on hand to tell you all about the one-eyed beast. Meanwhile, check them out on Facebook!

January 28th, 2013 § § permalink

The Mildred L. Batchelder Award is given to the most outstanding children’s book originally published in a language other than English in a country other than the United States, and subsequently translated into English for publication in the United States.

The award was announced today by the Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC), a division of the American Library Association (ALA), during the ALA Midwinter Meeting in Seattle. ALSC is the world’s largest organization dedicated to the support and enhancement of library service to children, with a network of more than 4,000 children’s and youth librarians, literature experts, publishers and educational faculty.

A Game for Swallows: To Die, To Leave, To Return published by Graphic Universe, a division of Lerner Publishing Group was selected as a Batchelder Honor Book. From Macey Morales’ article in American Libraries Magazine:

Originally published in French in 2007 as “Mourir Partir Revenir: Le Jeu des Hirondelles,†“A Game for Swallows: To Die, To Leave, To Return,†was written and illustrated by Zeina Abirached, and translated by Edward Gauvin. In her graphic novel memoir, Abirached focuses on one night during the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990) during which she, her brother, and their neighbors huddle in the safest corner of their apartment sharing memories, food and comfort.

“Stark black and white illustrations strikingly depict a caring community formed during the grim reality of war, creating an unforgettable memoir,†said Batchelder Award Committee Chair Jean Hatfield.

Congratulations to Dial Books for winning 2013 Award with My Family for the War, written by Anne C. Voorhoeve, and translated from German by Tammi Reichel. Congratulations as well to the other Honor Book, Son of a Gun (Eerdmans Books) by Anne de Graaf, who translated it from Dutch herself.

All my thanks to the members of the 2013 Batchelder Award Committee: Chair Jean Hatfield, Wichita (Kan.) Public Library, Alford Branch; Diane E. Janoff, Queens Library – Poppenhusen, College Point, N.Y.; Sharon Levin, Children’s Literature Reviewer, Redwood City, Calif.; Erin Reilly-Sanders, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio; and Judith E. Rodgers, Wayzata Central Middle School, Plymouth, Minn.

January 27th, 2013 § § permalink

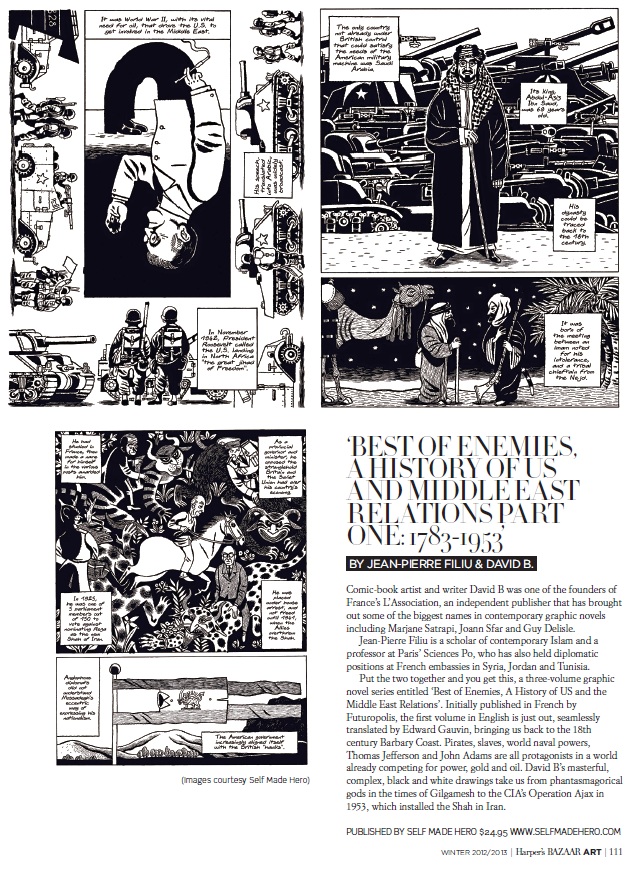

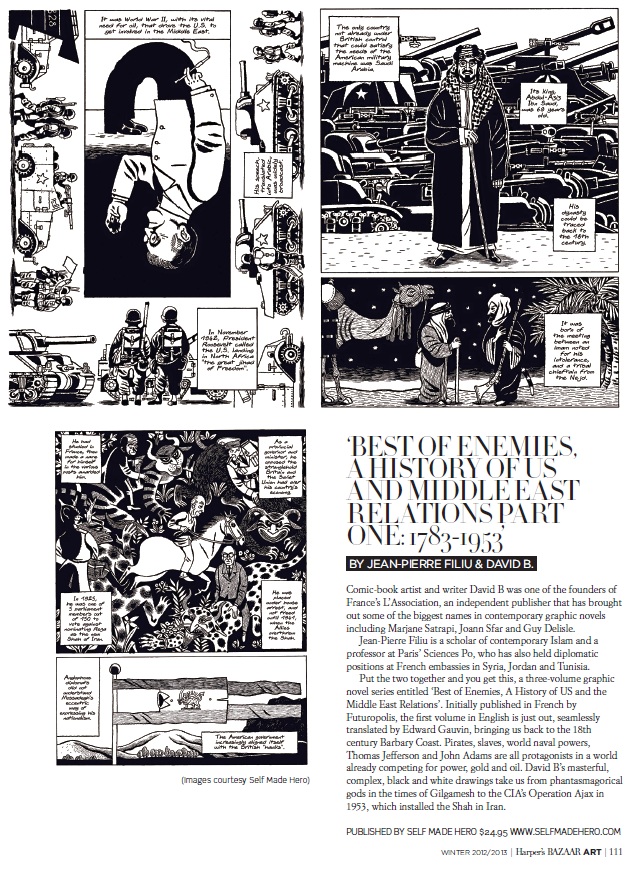

Under the editorship of Olivia Snaijie, the Winter 2012-2013 issue of Harper’s Bazaar ART, an Arabian sister publication, generously affords a full page to a review of David B. and Jean-Pierre Filiu’s Best of Enemies, including the kindest of nods to my translation:

January 25th, 2013 § § permalink

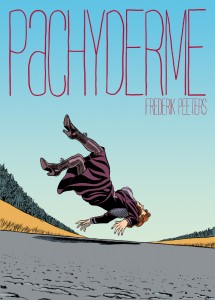

RHB at Forbidden Planet International (the blog of that famous chain of SFF/comics bookstores) has posted some astute acclaim for Frédérik Peeters’ Pachyderme.

But just because Peeters the artist fills his pages with beauty and disturbing imagery, Peeters the writer is not tempted to sit back. In fact, here with Pachyderme there’s plenty of story, and free-flowing natural dialogue abounds between the fascinating cast of characters. Everything works together to create something absolutely intense, a surreal, dreeamlike experience that Peeters throws about with such control.

Yes, it’s an artist’s story, but whilst some artist’s who write create nothing but visual wonder loosely held together with a bland, perfunctory story, there are those who utilise every bit of visual ingenuity and style they possess but then step up and create something dramatic that reads as beautifully as it looks. Thankfully Peeters is one of the latter.

Simply put, Pachyderme is a magnificent roller-coaster of emotional intensity, one of those narratives that grasps the mind, quickens the pulse, and simply doesn’t let go until the very end. Yes, there’s all that Lynchian influence thing going on, intentional or not, but influences worked out this well aren’t something to complain about.

I’d like to see this book get some more love, as it sort of slipped onto shelves late last fall from SelfMadeHero—their second Peeters book—but hasn’t really picked up the steam it so mightily deserves, despite a preface by no less than Moebius calling the book a masterpiece. This book is a genuine marvel, perfect from the first page to the last. I won’t say it’s been overlooked yet—it’s still early, and it hasn’t been out long—but with awards seasons coming up, this graphic novel could use some word-of-mouth and more reviews. Don’t let it suffer the fate of all too many a translation and sink from sight, without a trace, for lack of buzz! Find out more about it in my essay at Weird Fiction Review!

January 23rd, 2013 § § permalink

Continuing our coverage of A Chinese Life by Ôtié and Kunwu, Andrew Hertzberg at Frontier Psychiatrist (one of the few to include hanzi in his review) has a few reservations:

As A Chinese Life unfolds, it becomes clear that what it means to be Chinese has changed drastically over a relatively short period of time…

What A Chinese Life fails to do, however, is to consider if Li has changed his opinion of Mao since his youth. Likewise, it’s frustrating that Li never comes out to fully denounce his former overly-patriotic self. Further, he remains opinionless on the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989. Perhaps as it is just “a†Chinese life that he is trying to depict, he doesn’t feel the need to describe anything he didn’t experience firsthand. Still, for someone to claim to love his country as much as he does, one would hope he would have felt compelled to share an opinion on such a nationally and globally significant event.

Then again, as writers such as Ben Marcus have shown, what is not said is as important as what is said; similarly, in a graphic novel is what is not depicted just as important as what is depicted. This seems right in step with many people’s highest criticism of China’s government, that of covering up or not even trying to find out the truth. While Li admits his repression with four panels that fade to a few dots to represent his hazy memory, he at least is making the effort to want to remember. It’s not like he has to protect himself at this point. He had already, as a pre-teen, humiliated many teachers and businesses across his town, for being reactionaries or traditionalists.

Regardless, Li does a great job subtly transitioning from 1950s China into modernity, adding a few power lines here and there, more and more cars and skyscrapers, altering fashion and hairstyles, and eventually ubiquitous Western restaurants like McDonalds and KFC that have since taken over every city in the country. Considering how the book ends up visually, and what I know of my visits to China, the first two hundred pages are shocking in how recent of a time they depict. The illustrations of Li’s hometown of Kunming could just have easily been in the third century BC as in middle of the 20th century.

What A Chinese Life does best is to expose that what it means to be a Communist has changed over time. The hyper-conservative, history-negating, and overly-critical and paranoid members of the Chinese Communist Party in the 1950s and 60s is nothing like today’s open-armed, capitalist embracing, Western-admiring CCP of today. On the back sleeve of the book, Li is proudly listed as a CCP member. That certainly explains why he chose merely to display events just as they happened with little commentary of his own. Clearly, this is not a textbook (despite its girth) and shouldn’t be judged as one. While it could have been a masterpiece had it gone deeper and more critically into governmental policies, the fact that Li doesn’t shows the strong-arm the government still has over its people (especially for newspaper writers). While Li does his best to paint as well of a picture of Chinese life that he can, we’ll unfortunately always be left wondering how many other panels of the graphic novel have conveniently been “forgotten†by the author…

A Chinese life is full of smoking and mahjongg, massage parlors and snooker. A Chinese life involves puppy-love and funerals, celebration and protests, family and patriotism; A Chinese life is a political life. A Chinese life was, is, and will likely continue to be, a life in transition.

Reviewer Hillary Brown of Paste has a list of negatives:

Kunwu’s style—brushy, even sloppy, when it comes to depicting characters but better for landscapes and cityscapes—doesn’t assist the reader, either. Side stories can seem shoehorned in to illustrate particular developments, especially as Kunwu spent most of his life as a propaganda artist for the state and didn’t participate in political protest or the economic revolution. Most troubling of all is his persistent justification for problematic or horrific policies, as with the crackdown in Tiananmen Square in 1989 and the shrugging off of state-caused famine and the excesses of the Cultural Revolution. It’s not exactly a full-throated defense, but the man who ends the book hasn’t changed much from the little boy at its beginning who was devoted to Mao.

But David Luhrssen at Express Milwaukee counters

Chinese dissident artists get all the press in the West, and Li Kunwu is not among their ranks. Now a Communist Party arts administrator, he grew up during the hateful Cultural Revolution of the 1960s (his family members were among the millions of victims) and brings an unusual insider’s view to his autobiography in the form of a graphic novel. With brush strokes often suggesting Chinese calligraphy, he moves easily between styles, usually emphatic black ink on white backgrounds. The artist expresses some dismay at many developments, but his bottom line, after witnessing warfare, famine and massive state-sponsored violence, is a “profound desire for order and stability.†Armchair activists in the West may snicker, but most of them have had easy lives compared to Li Kunwu.

And writing at Comics Bulletin, Daniel Elkin rebuts Brown’s point about Kunwu’s art:

Yes, this book is a memoir. Yes, it is one man’s life. But A Chinese Life is an enormous story — as big as China itself, and I’m not just referring to its 704-page size. It is huge in terms of its intent and scope. Through one man’s story we see a culture go through dramatic social changes, its development following the same trajectory of maturation as Li Kunwu’s: from an infant revolution learning to walk and talk, to a petulant teenager obsessed with appearances, to finally adulthood with a greater understanding of social order and its place in the global community. A Chinese Life shows the development of a country as much as it does a man.

And it is within this collision that so much of the power of the story is found. As an outsider, especially an American, I became intrinsically engaged in this book from its very first page. This culture, so alien and so secretive and so…. well… foreign, comes to life in the pages of A Chinese Life in a profoundly personal and visceral way. The reader lives through the history of China as it watches Li Kunwu’s life unfold. And it is turbulent, and it is chaotic, contradictory and filled with conundrums.

But there is something else going on as well. As much as “progress” is constantly referred to in this book, there is still a harkening back. As much as the government tried to break with the past, that past was and is still so much of what makes China, “China.” Li Kunwu’s story circles like a whirlpool, sucking everything in to a new depth, but, in its velocity, detritus of the past bobs to the surface giving us something to grab on to so as to moor us as we float in the narrative. And we need these dinghies to keep us above water because, as I said earlier, this story is enormous.

Adding to the engagement is Li Kunwu’s art. Loose and expressive, evocative of Chinese calligraphy, Li Kunwu’s brushstrokes flow across the page adding serenity in some panels, turbulence in others, but there is always a sense of movement, progress, of “never going back.” At times Li Kunwu leaves large swaths of the page a stark white indicating a vastness to the landscape that details would delineate too much. Other times there is a cacophony of lines, a confusion of shapes, a hubbub, a swirl of activity — here the claustrophobia of the crush of the population is almost overwhelming, choking. Li Kunwu’s art engages all the senses with what he chooses to express as much as what he chooses not to show.

January 21st, 2013 § § permalink

Last September, SelfMadeHero published the 3 original volumes of A Chinese Life in a single massive tome. Reviews have been slow in coming, and naturally run long, but 700 pages is a lot to cover. It’s instructive to see some constants, both positive and negative, emerge from these detailed and considered reviews, admirable in the depth of their engagement with this deserving graphic novel—a monument, to be sure, but at 700 pages still but a mere sketch of the man’s life it’s meant to depict.

I’ve split this into two posts because the quotes are long. They’ll be posted a day apart.

At Page 45, reviewer Stephen pens a piece very sympathetic to Li Kunwu’s life and outlook:

A vital piece of social history brought vibrantly to life through Li Kunwu’s eye-witness account of all that he and his fellow village children instigated, propagated and then endured during the Cultural Revolution… right through to China’s meteoric industrialisation, modernisation, and the opening of its borders followed by Beijing’s triumphant Olympic games.

That it spans all six decades – of destruction and reconstruction – is key to the book’s success, bringing with it the contrasts and context vital to understanding how China is perceived by different generations of its own population, and in particular Kunwu’s very personal take which I found far from predictable as a Westerner. Seriously, you’re in for several surprises… You won’t believe it until you read it.

To his credit the artist and narrator shies not away from his own culpability, but his brilliance is in effectively helping us understand how it all came to this: the tiny details of their lives which foreshadowed what was to come.

Li is far more a witness than a commentator. He declines to cover the events of Tiananmen Square because, he says, he wasn’t even there (but that scene with his co-writer Philippe Ôtié shows him wriggling apologetically to avoid it – it was obviously a bone of contention), and you won’t see Tibet mentioned once. He’s far prouder of what China has accomplished in thirty-five short years and, as I say, once you’ve read the first half for yourself you will probably understand why.

There’s much to admire in the art with its fine sense of space, and which grows more precise rather representational the closer we move to the present. Some of the architecture is stunning (just flick to page 587 for a nocturnal courtyard of illuminated beauty) while the landscapes he visits later on are… pfff… off the scale.

I’ve only scratched the surface, and it occurs to me now that because of graphic novels like this, FORGET SORROW, PERSEPOLIS, PYONGYANG, SHENZHEN, SILK ROAD TO RUIN, and FOOTNOTES IN GAZA that I’ve learned far more about geography and history outside of Europe through comics than I ever learned during over a decade spent at school. Stuff I really needed to know, told through enlightening personal perspectives.

Sebso at Comics, French side echoes these sentiments:

I must admit that I have always been unable to figure out what these people think of their own history, how they feel about their country, about their leaders, about the evolution of their society.

Here lies the great quality of A Chinese Life. Li Kunwu is a Chinese artist whose father took part in every phase of the Chinese Communist Party since the Second World War. Based on Li Kunwu’s memories, Philippe Ôtié, a French writer, drafted a storyboard that was drawn by Li Kunwu himself. This close collaboration was successful and the resulting graphic novel is very pleasant to read: The story is clear and easy to follow, even for someone not specialized in Chinese history (whereas the historical events told are very complicated…). Li Kinwu’s art, with a strong influence from his Eastern formation, is original and nice.

A Chinese Life may not be a great masterpiece but it gives a fascinating insight into how it can feel like to have led a Chinese life for the past few decades.

Blogger HardlyWritten (one of the few to credit the translation) says:

Though not perfect as a historical reference – and never intended to stand alone as historical reference – this tale provides an entertaining portrayal of the experiences of a common man living through the Chinese struggle to become recognized as a world power in the 20th and 21st century. Living among the poor villagers of China’s Southwest, Li Kunwu grew up during Mao’s revolution of the 1950′s, suffered through the disasters of famine that resulted from the poorly managed Great Leap Forward, served in the People’s Liberation Army during the expansion of the country’s borders, and befriended the social elite during the economic expansion of the 80s-present day.

At times Li’s storytelling is humorous… At times Li’s storytelling depicts an unsettling sadness… No matter what you think of China’s history and its current status as a world power, this book is successful in depicting the Chinese people for what they are, a people living together through tumultuous and trying times, people afflicted with aspirations and naivete, afflicted with hope and the endurance to continue on and work for something greater for their children. Although this 60 year story largely ignores China’s fragile relationship with Taiwan and Tibet and only briefly mentions Tienanmen square, Li acknowledges these weaknesses by openly accepting that this is a story of his life, a single man, and no single man lives through all the history of his entire country (he didn’t know anyone affected by Tienanmen and therefore had little to say). Li is upfront about his artistic background as a party propaganda man, and in my reading I was cautious about a slanted tone, but this book is not propaganda, it is utterly honest and human, willing to demonstrate weaknesses and failures alongside triumphs and accomplishments.

January 19th, 2013 § § permalink

Italian comics master Sergio Toppi passed away in August. In December, Archaia released his first work in English, Sharaz-De, a retelling of the Thousand and One Arabian nights. It may seem odd that for a book of overwhelming visual appeal I’m going to do a largely imageless post, but the blog coverage has been so thorough that it’s a job best left to them. So please click through to be dazzled!

First, a preface from Illustrators’ Lounge apropos his passing:

Milanese illustrator Sergio Toppi began his career in advertising but by 1966 had moved into comics. Toppi accumulated a tremendous body of work during his career include titles such as Collezionista (“Collectorâ€), Linus, Corto Maltese and many one-shot comics during his long-term collaboration with writer Il Giornalino. His style is unmistakeable, geometrically dominated with loose sketchy pencil work. A fantastic amalgamation of tone, patterns and texture.

At Comics Bulletin Jason Sacks has only the highest praise:

The word “visionary” is sometimes thrown around too liberally in the arts. I often find myself using the term to describe a creator whose work is just a bit different from the mainstream, innovative in small but interesting ways that move their medium ahead, or to the side, or at a distinct angle, but still within comfortable confines. It takes a certain kind of artist to reveal to me what it means to be a true visionary in the comics field.

Sergio Toppi is a true visionary, and his Sharaz-De: Tales from the Arabian Nights is a true visionary work. In all my years reading comics I’ve never read something quite as unique, odd and intriguing as this book.

The encomium continues in detail with Greg Burgas of Comic Book Resources:

It’s Toppi’s magnificent artwork, however, that makes this a must-buy. Walt Simonson wrote the foreword to this book, and it’s not surprising that Simonson writes about how much he loves Toppi’s work – Toppi is obviously a big influence in Simonson’s art. I don’t even know if I can write about his artwork well enough to do it justice. Toppi is amazingly detailed, as the desert world in which the book is set comes to magnificent life under his pen, and his use of swirling lines make it even more Asiatic and lustrous. This is an “Orientalist,†archaic view of the Arab world, but it’s still marvelous. Toppi’s characters are bold and striking, with a mixture of Semitic and African characteristics, and Toppi adorns them in gorgeous robes and armor and headgear that turn them into gods on earth, easily able to contend with the demons and djinn who also populate the book. He uses negative space beautifully, and his page compositions are superb – he uses panels, but he also often blends several scenes together in one splash page that remain remarkably easy to read. His creatures are beautiful – enormous and occasionally grotesque, but also marvelously ornate and perfectly suited for the magical world that Sharaz-De embroiders every night. Toppi experiments with some colors in the book, and those are wonderful, too – deep blues and purples and greens turn the desert at night into a mystical place, while the rich browns and yellows of the clothing during the day make the characters almost a part of the landscape. It’s an amazingly sensual book, packed with precise details and expansive vistas and fierce characters, and perhaps the only one who comes close in American comics is Simonson himself.

Publishers Weekly echoes these sentiments:

Two chapters are given over to vibrant watercolors, adding a psychedelic undertone to the tightly woven ink work elsewhere, as jinn, devils, and selfish men do battle upon the pages. Toppi does not use conventional comic panels, but allows his illustrations to sprawl behind and around them, with a singular illustration depicting multiple aspects of the story depending on where your eye first lands. A foreword from Walter Simonson pays tribute to the artist, who died in August, 2012. The Tales from the Arabian Nights may be well enough known, but Toppi’s unparalleled skill at twisting fine art, design, and comic book structure together render this a real treat.

And in the most recent review, Scott Vanderploeg of Comic Book Daily concurs:

Of course one look at the images included and you’ll see it’s Toppi’s art that steals the show. It’s beautifully done, detailed and immersive. The layout and design of the pages provide so much detail to the tale that it’s hard to tear yourself away to turn the page. Everything flows seamlessly, no matter what aspect of graphic storytelling used.

January 14th, 2013 § § permalink

Good news, everyone!

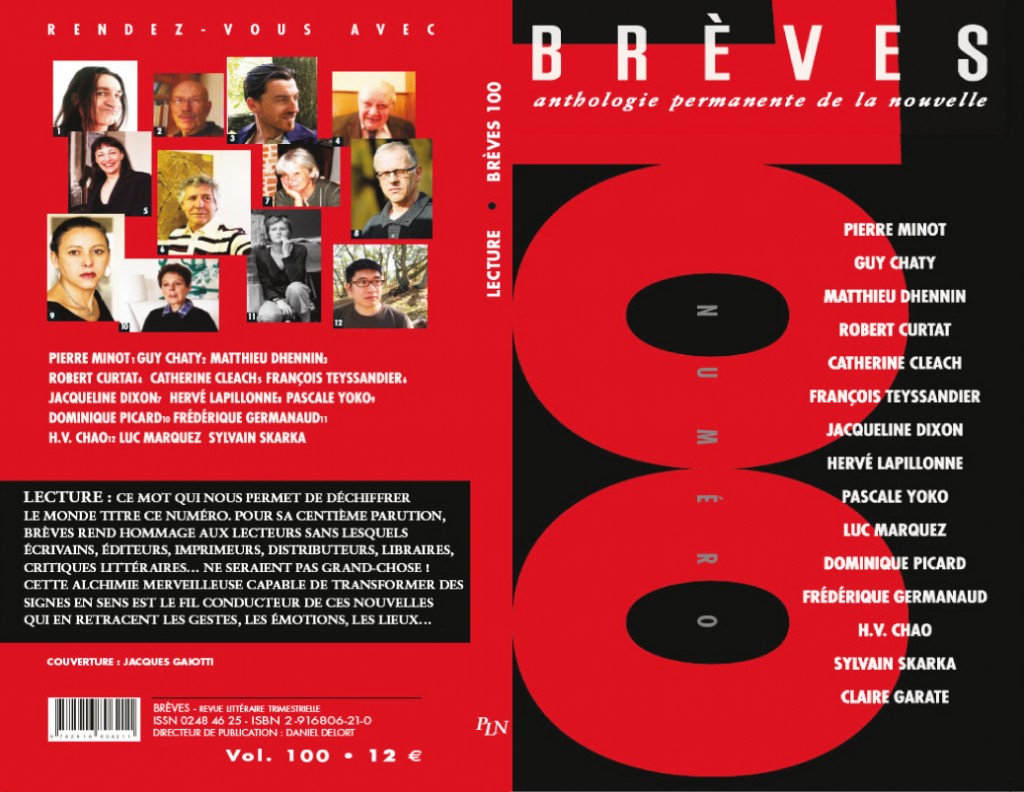

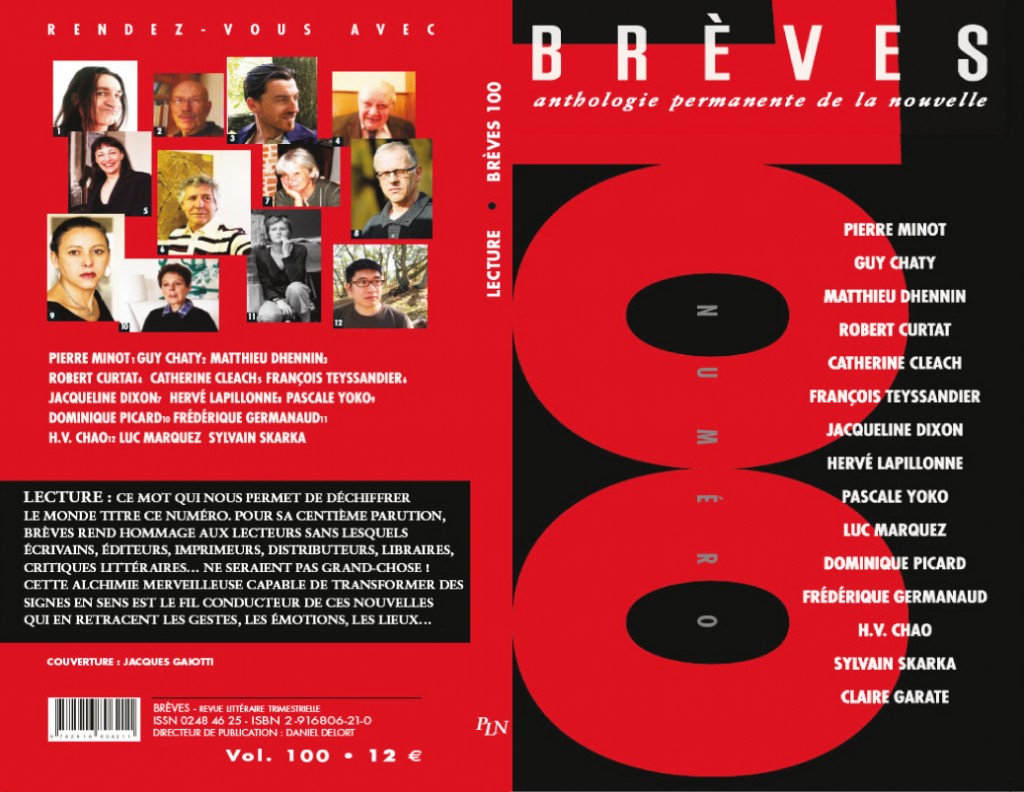

Copies of the 100th issue of Brèves featuring Georges-Olivier Châteaureynaud’s translation of H.V. Chao’s story “My Father’s Hand†and much much more, are available for order at

Revue Brèves

1, rue du Village

11300 Villelongue d’Aude

France

12 € covers domestic French postage. A snapshot of the contemporary French short story!

Pour recevoir franco de port et par retour de courrier, un ou plusieurs exemplaires de ce numéro, il vous suffit d’envoyer vos nom et adresse avec la mention « pour le numéro 100 » accompagnés du chèque correspondant : 12 € par numéro.

… à notre adresse : Revue Brèves, 1, rue du Village, 11300 Villelongue d’Aude

January 13th, 2013 § § permalink

Bad news first: so, the holiday seasons were fraught. My laptop was broken, then stolen, making me egregiously late with work for several clients; we were forced to replace a total of three tires and a rim on our 2004 Ford Taurus; and I am currently in my second cold in four weeks. But I can only hope this means all available luck is being funneled toward grant and fellowship applications!

But on to terrific news: congratulations to Fabien Vehlmann and Gwen de Bonneval for making this year’s Publishers Weekly Year’s Best list with their far-future SF Last Days of an Immortal (Archaia), thanks to John Seven’s Starred Review. Author Stephen C. Ormsby also gives it a nice nod at his blog, and it is featured at the French Embassy’s Education Site.

Congratulations as well to David B. and Jean-Pierre Filiu for making Honorable Mention with the first volume of their history of U.S.-Middle Eastern relations, Best of Enemies (SelfMade Hero). Chris Mautner of Comic Book Resources singles out David B.’s art for praise:

His art serves as a reminder and stern rebuke to lax publishers and artists about how to properly bring history to life.

Andrew A. Smith of The Telegraph chimes in as well:

Sometimes a graphic novel arrives that’s more important for what it teaches than how it entertains… “Best of Enemies†is invaluable for the U.S., because as a country, we are broadly ignorant of what our political and corporate leaders have been doing for the last 200 years in the most volatile region on Earth.

Finally, Sean T. Collins of The Comics Journal offers a close, savvy analysis of Othering and the politics of representation in David B.

The genius of David B.’s comics about violent conflict between cultures and faiths — and Best of Enemies, his collaboration with historian Jean-Pierre Filiu, is very much in that tradition, alongside the war-story sections of Epileptic or the heretic fables of The Armed Garden — is that he Otherizes everyone. To flip through this volume, which traces the history of the United States’ dealings with the Middle East from the fledgling democracy’s conflicts with North Africa’s Barbary pirates at the turn of the 19th century through the CIA overthrow of the Mossadegh government in Iran in the 1950s, is to encounter a panoply of fantastical figures, whether they’re wearing turbans or tricorner hats.

B. is one of contemporary comics’ true visionaries, the speaker of a visual language of his own devising. Despite personal, cultural, and surface-visual connections (all that high-contrast black-and-white) that might make it look otherwise, as an image-maker he has much more in common with, say, Jack Kirby than with Marjane Satrapi. This gives everyone and everything he depicts a hyperreal aura, and in Best of Enemies he goes full-throttle on it. The headdress of an imperious ambassador becomes a globe the pirate ships whose attacks he permit circumnavigate. A stand-in for the WWII-era British government becomes a three-faced Janus-like figure, issuing contradictory proclamations about the future of the region out of every mouth. The chronically bedridden Mossadegh becomes a disembodied set of pajamas, wielding a scimitar against the floating Sauron-like eyes of British spies and provocateurs.

January 8th, 2013 § § permalink

Americans are wont to envy Europeans their government arts funding and the cultural prestige still afforded writers, but the French rightly envy our many venues for short fiction. Lament as we might dwindling readerships, or question the fallout of university patronage, the literary journal has kept a certain short story culture alive stateside, and beyond its sphere genre magazines are similarly thriving.

Since 1981, the revue Brèves has been leading the good fight in France, part of the short story résistance that followed in the wake of the 1970s short story renaissance. Wonderfully edited, with its theme issues devoted to genre, country, and single authors, it’s proven time and again a great resource for researching and reading short fiction, a somewhat underdog form in France. Now among the nation’s premier short story reviews, it is celebrating its 100th issue, and I am delighted to report my good friend H.V. Chao’s name graces the cover. Georges-Olivier Châteaureynaud generously translated his story “My Father’s Hand.â€

This mark’s Chao’s second appearance in French; the first was Fall 2011, in the fantastical revue Le Visage Vert. There Anne-Sylvie Homassel rendered as “Le Joyau du nord†his story “Jewel of the North,†first published in the Fall 2009 issue of Epiphany. I was last reminded of this tale over Thanksgiving, when the news surfaced that

amid the blizzard of paper scraps that flurried down during last Thursday’s parade were some details that should never have been put into public hands – never mind let flutter through the streets of New York City.

Social security numbers, police detail assignments, and incident reports were all visible on the confetti strips dumped along the parade route at 65th and Central Park West on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

In Chao’s story, an unexplained rain of ash gives way to bits of paper:

A few days later, the first scraps fell: the curled edge of an almanac, half a canceled stamp, a charred bit of receipt with a price still partly legible. At the café Anya, frowning, fished the scorched end of a ticket stub from the tea dregs at the bottom of her cup. Some believe these tatters, with their evidence of daily lives, an attempted message met en route with accident.