April 29th, 2015 § § permalink

Pakistani literary journal The Missing Slate has published my translation of Jean Muno’s flash fiction “The Chair”! Here’s an excerpt:

Stranger still: the chair was only there till it wasn’t. This happened more or less quickly, and always unexpectedly. It took advantage of a moment’s inattention, a brief absence on Frederick’s part, to vanish, so quickly that he’d never actually seen it vanishing. Every morning for two weeks now, the chair had escaped him. He would have had to keep an eye on it without let-up, not look away before the sun was fully up, but he had neither the patience nor the leisure.

Jean Muno is the greatest of Belgium’s Silver Age fabulists, heir to Jean Ray and Thomas Owen. His ever-wicked humor skewers the absurdity of the suburbs and their spiritual emptiness. The author of nine novels and four story collections, he received the Prix Rossel in 1979, and was a member of Belgium’s Royal Academy of Languages and Literature. His work has appeared in Weird Fiction Review and is forthcoming in Year’s Best Weird Fiction Vol. 2.

April 27th, 2015 § § permalink

Issue 18 (Fall/Winter 2014) of the erstwhile Subtropics features Bernard Quiriny’s story “A Neverending Bender,” the fourth story I’ve published from his multi-prizewinning 2008 collection Contes carnivores. Here’s an excerpt:

When my brother and I were children, Dad had a safe in his office where he hid his papers, money, and a revolver. The office was off-limits; John and I were not allowed to set foot inside. But one day, our games led us there. The safe was open, and I remember catching sight of a little bottle which, habitué that I was of falling off bikes, I took for astringent. (That very night, I gave myself away by telling my father that he should keep the bottle in the medicine cabinet, thus revealing that I’d disobeyed him.)

What did that bottle contain? In light of the manuscript we’ve just seen, I find it hard to believe it wasn’t zveck.

Belgian Bernard Quiriny (1978 – ) is the author of three short story collections: L’Angoisse de la première ligne (Phébus, 2005), which won the Prix Littéraire de la Vocation; Contes carnivores (Seuil, 2008), which won Prix du Style, the Prix Marcel Thiry for fabulism, and Belgium’s top literary prize, the Prix Rossel; and Une collection très particulière (Seuil, 2012), which won the Grand Prix de l’Imaginaire. He has also written two novels: Les assoiffés (Seuil, 2010), a satirical dystopian alternate history of Belgium as a feminist totalitarian state, and most recently Le village évanoui (Flammarion, 2014), as well as a biography of symbolist poet Henri de Régnier, Monsieur Spleen (Seuil, 2013). His work has appeared in English in Subtropics, World Literature Today, The Coffin Factory, Weird Fiction Review, and Dalkey Archive’s Best European Fiction 2012.

April 25th, 2015 § § permalink

The Missing Slate, a Pakistan-based online litmag “for the discerning metropolitan,†was created with intent to uphold free speech irrespective of geography, political or religious affiliations.

Our goal is simple: honor talent and incorporate as many styles, opinions and cultures as possible. The magazine is a “borderless†one with a culturally and intellectually diverse team that believes if art can’t be quantified, it can’t be mapped either.

They were awesome enough to feature a a deep cut from the Georges-Olivier Châteaureynaud archives: the first story from his first collection, the 1973 triptych entitled Le Fou dans la chaloupe [The Madman in the Rowboat]. “His Final Pages†is a Borgesian mindbender, and a fitting meditation on mortality from a writer who, even as an young man, was concerned with an old man’s questions of death, debility, and the writing life, and the hollowness of success. Here’s an excerpt:

This much I have always known: to write is a disgrace. Don’t they know, who boast of it naively, that in every age it has mainly drawn the weak and mediocre, the spineless, eccentric, and effeminate, who found no other fitting activity? A man sound of mind and body does not write; he acts on, delights in, the real. Blessed are they who forget—screwdriver, bazooka, or slide rule in hand—the ulcerous idleness of the universe, which unveils itself upon the slightest inspection. When I was thirty, the air that seemed to intoxicate everyone else gave me no joy to breathe. I was waiting for that illness to declare itself, the illness that would save me: a book.

Widely known in his native France, Georges-Olivier Châteaureynaud (1947- ) has been honored over a career of almost 40 years with the Prix Renaudot, the Prix Goncourt de la nouvelle, and the Grand Prix de l’Imaginaire at Utopiales. He has been published in Conjunctions, The Harvard Review, The Southern Review, Words Without Borders, AGNI Online, Epiphany, Fantasy & Science Fiction, Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, Postscripts, Eleven Eleven, Sentence, Joyland, Confrontation, The Brooklyn Rail, Liquid Imagination, Podcastle, and The Café Irreal, as well as the anthologies Exotic Gothic 5 (PS Publishing, 2013) and XO Orpheus (Penguin, 2013). His volume of selected stories, A Life on Paper (Small Beer, 2010), won the Science Fiction & Fantasy Translation Award and was shortlisted for the Best Translated Book Award. His work has been compared to that of Kafka, Borges, Calvino, Cortazar, Isak Dinesen, and Steven Millhauser.

Like it? Consider buying Châteaureynaud’s volume of Selected Stories, A Life on Paper!

April 23rd, 2015 § § permalink

The latest issue of The Literary Review, dedicated to John le Carré, features a naughty bit of local color from ’50s Paris: an excerpt from Jean-Paul Clébert’s recently reprinted underground classic Paris insolite [Curious Paris], a memoir of homeless life in Paris said to have influenced Henry Miller and the Situationist principle of the dérive. Published in 1952 with a dedication to Robert Doisneau and photographs by Patrice Molinard, it was, in the author’s own words, “not a story in the journalistic sense, but a personal investigation.†It’s a freewheeling book, like On the Road. The excerpt is entitled “The Bawdyhouse for Beggars.” Here’s the opening:

BEFORE THE WAR there was, I think, in the Saint-Paul neighborhood on rue de Fourcy, a most astonishing public space, a whorehouse for hobos. This bedlam, now vanished from the earth if not its clients’ memories, whose sorely missed atmosphere can be readily imagined, consisted of two rooms-the Senate, where the rate was ten francs across the board, and the House of Representatives, where it hovered, according to mood and quality, around fifteen.

Jean-Paul Clébert (1926-2011) is the author of more than forty works of fiction and nonfiction. He left Jesuit school at 16, to join the French Resistance, and afterward, traveled Asia. In the 1950s, he frequented two related movements—dwindling Surrealism and burgeoning Situationism—as well as reporting from Asia for Paris Match and France Soir. The 1996 Dictionnaire du surréalisme, for which he single-handedly composed every entry, is widely considered a classic, as is his first book. Among other prominent works are The Blockhouse (1958), his only translated novel, and 1962’s Les Tziganes, a pioneering sociological study of Gypsies also based on personal experience, translated into English by Charles Duff (Dutton, 1963). His later works were dedicated to the history, nature, and culture of Provence, where he spent his final years.

April 21st, 2015 § § permalink

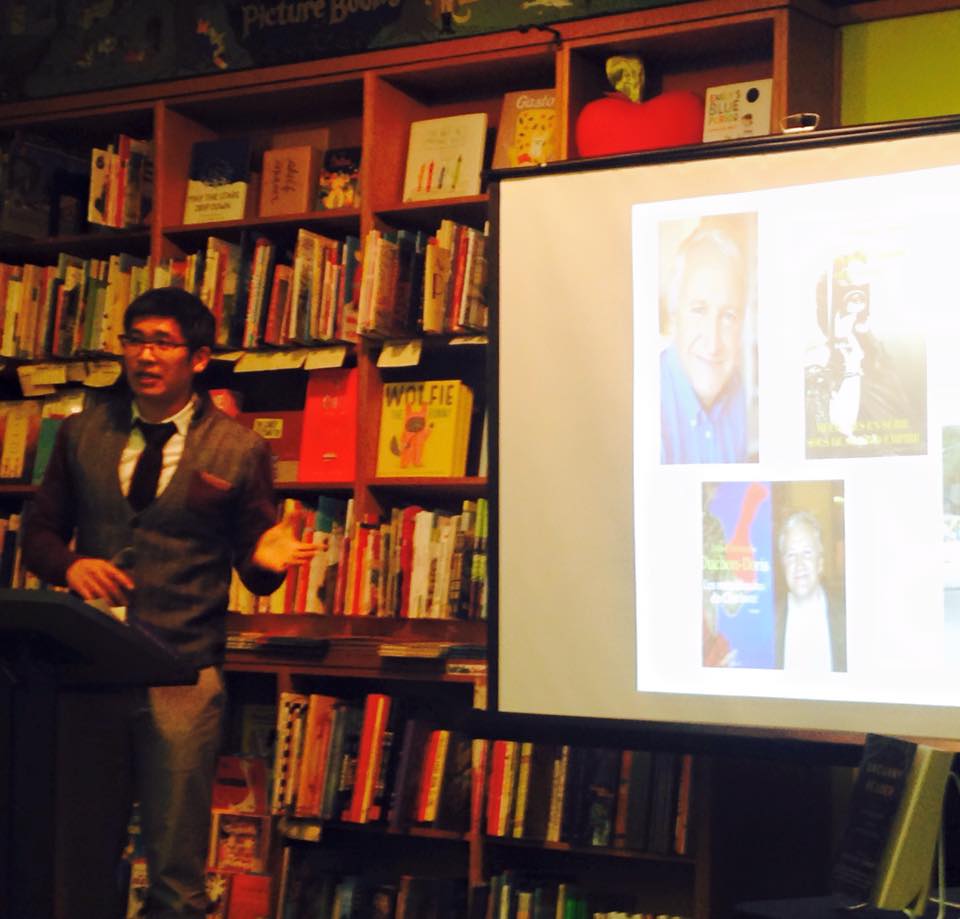

Last month I had the pleasure of giving a reading at San Francisco’s The Booksmith for The Uncanny Reader, in the company of editor Marjorie Sandor and fellow contributor Namwali Serpell.

Marjorie Sandor shared some etymological musings on the word “uncanny,” a version of which can be found at Weird Fiction Review. Namwali read from her Best American 2009 story “Muzungu,” and I read from one of two translations in the collection, “The Puppets” by Jean-Christophe Duchon-Doris, the author’s English-language debut. Here’s an excerpt:

Outside, it started raining even harder. Torrents of water hammering the tin roofs hid a quiet, almost mechanical background hum. And as you were both suddenly solemn, deeply focused, still—from time to time you merely brushed back an unruly lock of hair, while he, sparing with his motions, let his head sway to the ostensible rhythms of reading, turning the page only with infinite caution—you might have been mistaken for a pair of clockwork creatures. Stark light from the sky lit your faces, seeming to freeze time, while your springs ever so gently wound down like figures on a music box.

As the story was drawn from a collection of stories that chronicle the underside of Baron Haussmann’s renovations of Paris, I gave a brief historical slide show with period maps locating the story’s action, and told a slightly off-color translation story. You had to be there.

Trained as a lawyer, Jean-Christophe Duchon-Doris (1960 – ) is a presiding judge at the administrative court in his native Marseilles. Among the dozen books to his name are several popular historical mysteries featuring, in one instance (Les Nuits blanches du chat botté – The Sleepless Nights of Puss-in-Boots), a serial killer copycatting the fairytale of Charles Perrault, and in another (Le Cuisinier de Talleyrand: Meurtre au congrès de Vienne – Talleyrand’s Chef: Murder at the Congress of Vienna), Napoleon’s chef Antonin Carême, who is credited with inventing haute cuisine, as well as a trilogy featuring the royal prosecutor Guillaume de Lautaret and his witty wife Delphine d’Orbelet.

He has also written three short story collections, with a fourth on the way. The conceit of his Goncourt-winning second collection short stories, Les lettres du Baron(Juillard, 1994; The Baron’s Letters), is that its interconnected tales are based on letters that never made it to their addressees, because Baron Haussmann’s renovations had destroyed so much of Paris.

Also, be sure to check out the conversation with Marjorie Sandor at Weird Fiction Review!

April 19th, 2015 § § permalink

I’m proud to report my translation of Eugène Savitzkaya’s “In the Rediscovered Book,†first published in Anomamalous, was selected for inclusion in the Best of 2014 list from wigâ—leaF, a magazine of [very] short fiction. Here’s an excerpt:

In the book rediscovered in the drawer of the Gordon press, in the white cellar of the house on the mountains in the land that knew so many plagues and disasters, you saw trucks rolling down a muddy road, their enormous wheels splattering cyclists, many cyclists, red, blue and green; you saw quite low over the woods the balloon in flames, and in a well-mown meadow, fallen oxen washed by rain; you saw, sitting on a stone shaped like an oval table, a young girl wearing a crown made from natural palm leaves soaked in varnish, plastic ivy leaves and pearl flowers, wearing a great black wool damask paletot, lined with gray squirrel glistening with dew, but browned in spots.

Born in 1955 to parents of Ukrainian descent, Belgian Eugène Savitzkaya began publishing poetry at the age of 17. He has written more than forty books of fiction, poetry, plays, and essays, many of them published by Minuit, France’s leading avant-garde press. He received the Prix triennal du roman for his 1992 novel Marin mon coeur. Rules of Solitude (Quale Press, 2004; trans. Gian Lombardo), a collection of prose poems, was his first book in English. My translations of his work have appeared in Anomalous, Unstuck, Gigantic, and Drunken Boat.

April 17th, 2015 § § permalink

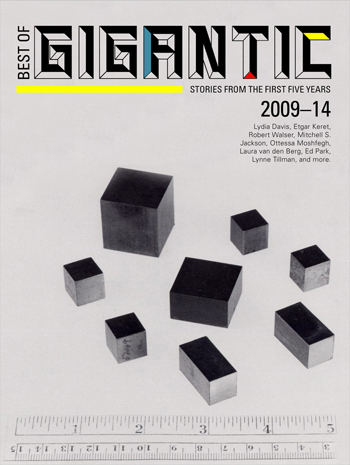

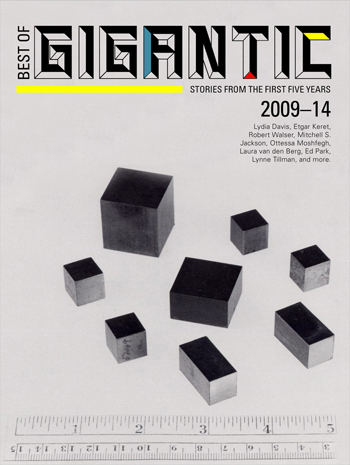

The tiny, mighty magazine of tiny, mighty fiction known as Gigantic has released a Best Of retrospective of its first five years (2009-14). I’m proud to report my translation of Jean Ferry’s “Rapa Nui” was selected for inclusion. Here’s an excerpt:

Since I had been thinking about it for thirty years, you would think I’d worked out my schedule in advance. Besides, I had no time to lose, as the Chilean training ship that had brought me was only putting in at port for two days. I am not lying when I say I was trembling with emotion under a strange, pale sun; I had a very hard time convincing myself this wasn’t the same old dream again, the dream where I dream I’ve reached Easter Island, trembling with emotion under a strange, pale sun. But no, it was all real: the wind, the black cliff, the three rippling volcanoes. There really were no trees, no springs. And, faithful to a date set at the dawn of time, the great statues awaited me on the slopes of Rano Raraku.

Like it? Consider purchasing Ferry’s short story collection The Conductor, from Wakefield Press.

April 15th, 2015 § § permalink

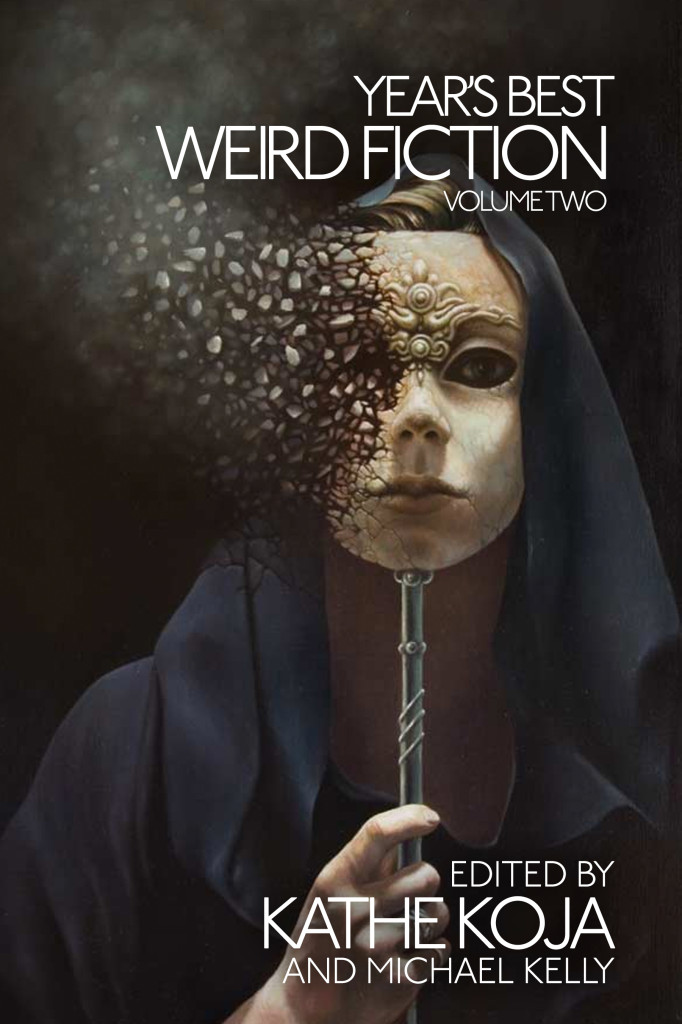

Undertow Books has undertaken the great task of rounding up the Year’s Best Weird Fiction. Editor Michael Kelly’s anthology series will showcase the “varying viewpoints†of this “diverse and eclectic mode of literature†with little if any overlap with the various other “Best Of†anthologies. From the publisher’s site:

What is weird fiction?

The simple answer is that it is speculative in nature, chiefly derived from pulp fiction in the early 20th century, whose remit includes ghost stories, the strange and macabre, the supernatural, fantasy, myth, philosophical ontology, ambiguity, and featuring a helping of the outré. Weird fiction, at its best, is an intersecting of themes and ideas that explore and subvert the laws of Nature. It counts among its proponents older and newer writers alike: Robert Aickman, Laird Barron, Charles Beaumont, Ambrose Bierce, Octavia Butler, Ray Bradbury, Angela Carter, Neil Gaiman, Shirley Jackson, Kathe Koja, John Langan, Thomas Ligotti, Kelly Link, H. P. Lovecraft, and many others.

Weird fiction is not specifically horror or fantasy. And weird fiction is not new. It has always been present. That’s because it isn’t a genre, as such. This makes the prospect of defining weird fiction difficult, and perhaps ill advised. Weird fiction is a mode of literature that is present in other genres. Weird tales were penned long before publishers codified and attached genre labels to fiction. You can find weird fiction in literary journals, in horror magazines, fantasy and science fiction periodicals, and various other genre and non-genre journals and anthologies that are welcoming to speculative fiction of the fantastique.

Weird fiction is here to stay. Once the purview of esoteric readers, it is enjoying wider popularity. Throughout its storied history there has not been a dedicated volume of the year’s best weird writing. There are a host of authors penning weird and strange tales that defy easy categorization. Tales that slip through genre cracks. A yearly anthology of the best of these writings is long overdue.

I’m proud to report my translation of Belgian Jean Muno’s “The Ghoul,†first published at Weird Fiction Review in the summer of 2013, was selected for inclusion. It’s about time we got some Belgian back in the Weird! Huge thanks to series editor Michael Kelly and guest editor Kathe Koja! Here’s an excerpt:

And yet there’d been a cry. A wail, a call, something human.

I have been following this man for a long time. Step by step, keeping my distance, as a hunter does its prey. Because I am wary. Whatever happens, I don’t want to be involved, just a witness, as a dreamer of his dream.

Sometimes the man stops, turns around, but because of the fog, ever denser as the tide rises, he sees less and less. Neither the dunes nor the sea, neither his destination nor his starting point. Perhaps he has crossed the border, perhaps not — how to tell? He is alone on a meager stretch of beach without landmarks. The cry could have come from anywhere at all.

April 13th, 2015 § § permalink

Black Key Press’ Best Indie Lit New England, or BILiNE, has Kickstarted its second volume to life. Thomas Dodson’s print anthology series showcases the best fiction and poetry published by independent journals in New England. I’m proud to report my translation of Eugène Savitzkaya’s “In Memory of Tabacchino,†first published in Anomalous, was selected for inclusion. Here’s an excerpt:

Tabacchino was a child. Tabacchino was a dormouse. Tabacchino was a dog, a bird, a squirrel, an almond tree, a living being. Child, dog, dormouse, bird, squirrel, or almond tree, he breathed, drank water, had a clean smell, a unique charm, and grew old. He bore inside him sap that flowed groundward through openings planned and improvised. The wind would muss his hair, rumple him, refresh and sometimes torment him. The first Tabacchino to get the coup de grâce was the almond tree: drought, then woodcutters. They wept then, lovers of almonds, the child first among them. No one could put the tree back as it had been. The dormouse, terrified by an owl, succumbed to a heart attack, rotted, and was scattered to the winds. Not the slightest sign of that bird in the skies now. Seek the dog’s grave in vain. Then came the child’s turn: crushed, ground, and scattered.Â

Born in 1955 to parents of Ukrainian descent, Belgian Eugène Savitzkaya began publishing poetry at the age of 17. He has written more than forty books of fiction, poetry, plays, and essays, many of them published by Minuit, France’s leading avant-garde press. He received the Prix triennal du roman for his 1992 novel Marin mon coeur. Rules of Solitude (Quale Press, 2004; trans. Gian Lombardo), a collection of prose poems, was his first book in English. My translations of his work have appeared in Anomalous, Unstuck, Gigantic, and Drunken Boat.

April 11th, 2015 § § permalink

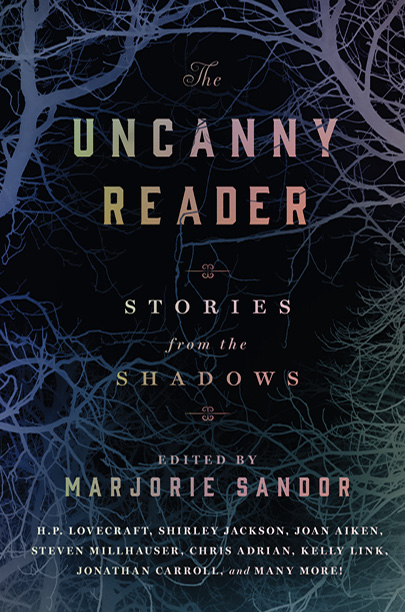

I have two translations in Marjorie Sandor’s new whopper of an anthology, The Uncanny Reader, which came out last month: the English debut of Jean-Christophe Duchon-Doris with his story “The Puppets,” and a re-translation of Guy de Maupassant’s “On the Water.” See the spooky book trailer here!

From the deeply unsettling to the possibly supernatural, these thirty-one border-crossing stories from around the world explore the uncanny in literature, and delve into our increasingly unstable sense of self, home, and planet. The Uncanny Reader: Stories from the Shadows opens with “The Sand-man,” E.T.A. Hoffmann’s 1817 tale of doppelgangers and automatons–a tale that inspired generations of writers and thinkers to come. Stories by 19th and 20th century masters of the uncanny–including Edgar Allan Poe, Franz Kafka, and Shirley Jackson–form a foundation for sixteen award-winning contemporary authors, established and new, whose work blurs the boundaries between the familiar and the unknown. These writers come from Egypt, France, Germany, Japan, Poland, Russia, Scotland, England, Sweden, the United States, Uruguay, and Zambia–although their birthplaces are not always the terrains they plumb in their stories, nor do they confine themselves to their own eras. Contemporary authors include: Chris Adrian, Aimee Bender, Kate Bernheimer, Jean-Christophe Duchon-Doris, Mansoura Ez-Eldin, Jonathon Carroll, John Herdman, Kelly Link, Steven Millhauser, Joyce Carol Oates, Yoko Ogawa, Dean Paschal, Karen Russell, Namwali Serpell, Steve Stern and Karen Tidbeck.

Marjorie Sandor is the author of four books, including The Late Interiors: A Life Under Construction. Her story collection, Portrait of my Mother, Who Posed Nude in Wartime, won the 2004 National Jewish Book Award in Fiction, and an essay collection, The Night Gardener: A Search for Home won the 2000 Oregon Book Award for literary non-fiction. Her work has appeared in The Georgia Review, AGNI, The Hopkins Review and The Harvard Review among others. She lives in Corvallis, Oregon.