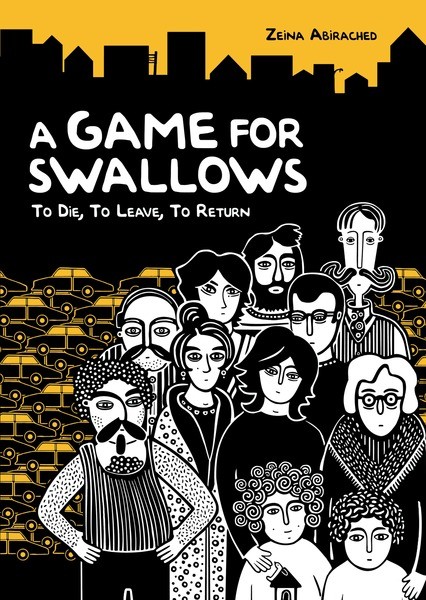

I’ve blogged about this before, but now the August 1st release date is finally nigh, I’d like to give another shout out to Zeina Abirached’s terrific graphic novel A Game for Swallows from Lerner Books. Words Without Borders featured the first ever English excerpt from the book in Feburary 2010, and PEN America, the journal of the PEN Foundation, soon published another. In 2010, A Game for Swallows was the first graphic novel to be selected for a grant by the French Voices Program from the French Embassy, and this year, it was named a Junior Library Guild selection. Indefatigable Brit comic blogger Paul Gravett did an excellent interview/article in January of this year (featuring uncredited pages cribbed from WWB), which details some of Abirached’s background, the book’s publication history in France with Éditions Cambourakis, and the impetus for its creation, which the author makes the centerpiece of the book’s expanded preface.

At first glance, the parallels between Abirached’s Swallows and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis are obvious, and probably something many critics will remark on: memoirs of childhood by Middle Eastern girls drawn in a black and white, deliberately naïve style. To be slightly cynical, ever since Persepolis, American publishers have been looking for the next French graphic novel that would prove as big as Satrapi’s hit. But Abirached’s page layouts are much more formal, decorative, geometrically inspired, even ceremonial. One could even liken them to the wall hanging in the foyer of the family apartment that is one of the book’s major motifs.

Swallows takes place over the course of a single night in the safest (read: windowless) room of an apartment against the backdrop of war-torn Beirut. It eschews the chronological progression of most memoirs for a frame story: Abirached’s parents are off visiting her grandmother, while the children are at home with Anhala, a maid who’s been in the family for generations. When a sudden bombardment forces the parents to stay at the grandmother’s till the streets are safe again, the children are trapped at home, in a foyer that quickly fills up with neighbors seeking shelter. Carefully characterized with quirk, distinctive physical features, and anecdotes that have the ring of truth, these neighbors form a precarious community that makes a great stand-in for that of the besieged city at large. Tensions and tempers rise and fall in this huis clos, but objects and moments also serve as excuses to delve into memories, personal histories; in fact, memories (and to a lesser extent, imagination) are the only way out, the only way to transcend perilous and limiting circumstance, a fact that is in no small way the source of the book’s melancholy.

Another aspect of the book’s inventiveness, and a challenge in translation, was its use of original and unconventional onomatopoeia. It may sound odd to claim sound design is an important part of a graphic novel, but in this case, Abirached earns it, using tiny everyday sounds to shade character or ratchet up tension in moments of silence: the tweak of a mustache, the drip of a tap, shattering glass and distant explosions. Every noise is articulate.

For all its ultimately mournful celebration of ephemeral things—people, places, communities—Swallows is a book rigorously obsessed with physical space, something that comes through in page and panel alike. Abirached skillfully manipulates maps, floor plans, and frames to convey a sense of literal confinement and a desperate lack of options that figuratively translates to the same thing. She brilliantly animates the fleeting minor joys snatched from life in wartime, and the way it insidiously forces an intimacy with uncertainty. When the happy ending comes, the relief it gives is all the greater for the ever-present sense of contingency it keeps at bay, if only for one more night.

I’ve blogged about this before, but now the August 1st release date is finally nigh, I’d like to give another shout out to Zeina Abirached’s terrific graphic novel A Game for Swallows from Lerner Books. Words Without Borders featured the first ever English excerpt from the book in Feburary 2010, and PEN America, the journal of the PEN Foundation, soon published another. In 2010, A Game for Swallows was the first graphic novel to be selected for a grant by the French Voices Program from the French Embassy, and this year, it was named a Junior Library Guild selection. Indefatigable Brit comic blogger Paul Gravett did an excellent interview/article in January of this year (featuring uncredited pages cribbed from WWB), which details some of Abirached’s background, the book’s publication history in France with Éditions Cambourakis, and the impetus for its creation, which the author makes the centerpiece of the book’s expanded preface.

At first glance, the parallels between Abirached’s Swallows and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis are obvious, and probably something many critics will remark on: memoirs of childhood by Middle Eastern girls drawn in a black and white, deliberately naïve style. To be slightly cynical, ever since Persepolis, American publishers have been looking for the next French graphic novel that would prove as big as Satrapi’s hit. But Abirached’s page layouts are much more formal, decorative, geometrically inspired, even ceremonial. One could even liken them to the wall hanging in the foyer of the family apartment that is one of the book’s major motifs.

Swallows takes place over the course of a single night in the safest (read: windowless) room of an apartment against the backdrop of war-torn Beirut. It eschews the chronological progression of most memoirs for a frame story: Abirached’s parents are off visiting her grandmother, while the children are at home with Anhala, a maid who’s been in the family for generations. When a sudden bombardment forces the parents to stay at the grandmother’s till the streets are safe again, the children are trapped at home, in a foyer that quickly fills up with neighbors seeking shelter. Carefully characterized with quirk, distinctive physical features, and anecdotes that have the ring of truth, these neighbors form a precarious community that makes a great stand-in for that of the besieged city at large. Tensions and tempers rise and fall in this huis clos, but objects and moments also serve as excuses to delve into memories, personal histories; in fact, memories (and to a lesser extent, imagination) are the only way out, the only way to transcend perilous and limiting circumstance, a fact that is in no small way the source of the book’s melancholy.

Another aspect of the book’s inventiveness, and a challenge in translation, was its use of unconventional onomatopoeia. It may sound odd to claim sound design is an important part of a graphic novel, but in this case, Abirached earns it, using tiny everyday sounds to characterize with charm or ratchet up tension in moments of silence: the tweak of a mustache, the drip of a tap, shattering glass and distant explosions.

For all its ultimately mournful celebration of ephemeral things—people, places, communities—Swallows is a book rigorously obsessed with physical space, something that comes through in page and panel alike. Abirached skillfully manipulates maps, floor plans, and frames to convey a sense of literal confinement and a desperate lack of options that figuratively translates to the same thing. She brilliantly animates the fleeting minor joys snatched from life in wartime, and the way it insidiously forces an intimacy with uncertainty. When the happy ending comes, the relief it gives is all the greater for the ever-present sense of contingency it keeps at bay, if only for one more night.

Leave a Reply